NationalEclipse.com | May 8, 2024 | National Eclipse Blog

It's already been a month since the long-awaited and much-anticipated 2024 total solar eclipse swept across North America. And what a wild eclipse it was! With eclipse excitement having ebbed to near-normal levels, the one-month mark seems like a good time to provide an overall summary, and my own personal account as a veteran eclipse chaser, of how this eclipse went down and what was learned.

The Weather

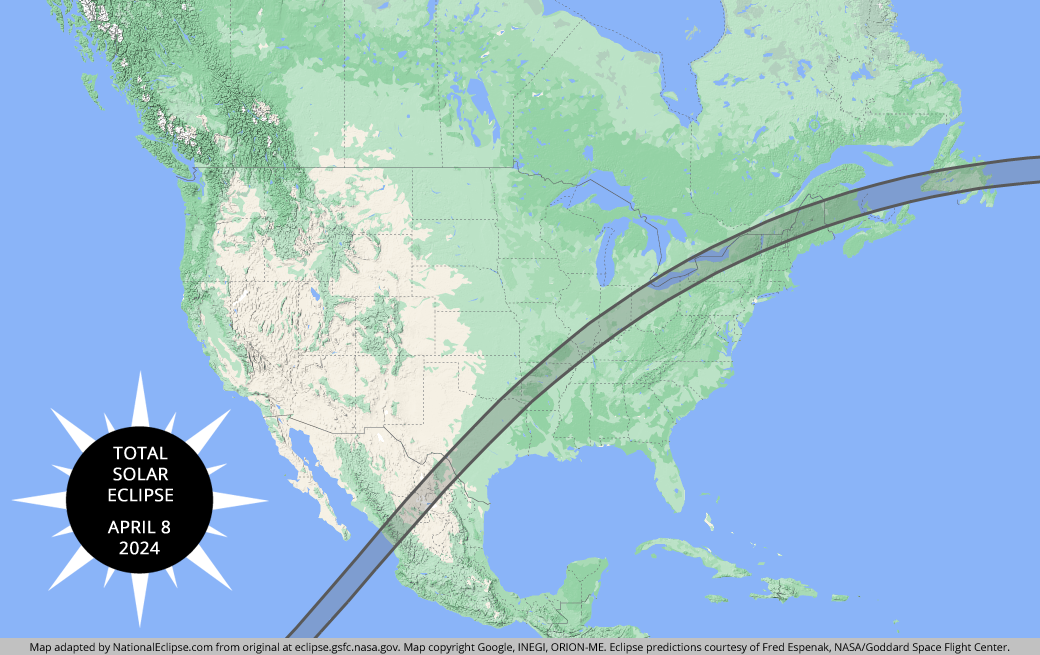

Let's start with the weather. Perhaps like no other total solar eclipse in recent memory, this one flipped the script on all of the long-term weather projections. For years now, weather experts have been telling us that the odds for a successful eclipse viewing on April 8 were best in Texas and worst in Maine. As it turned out, the exact opposite came true!

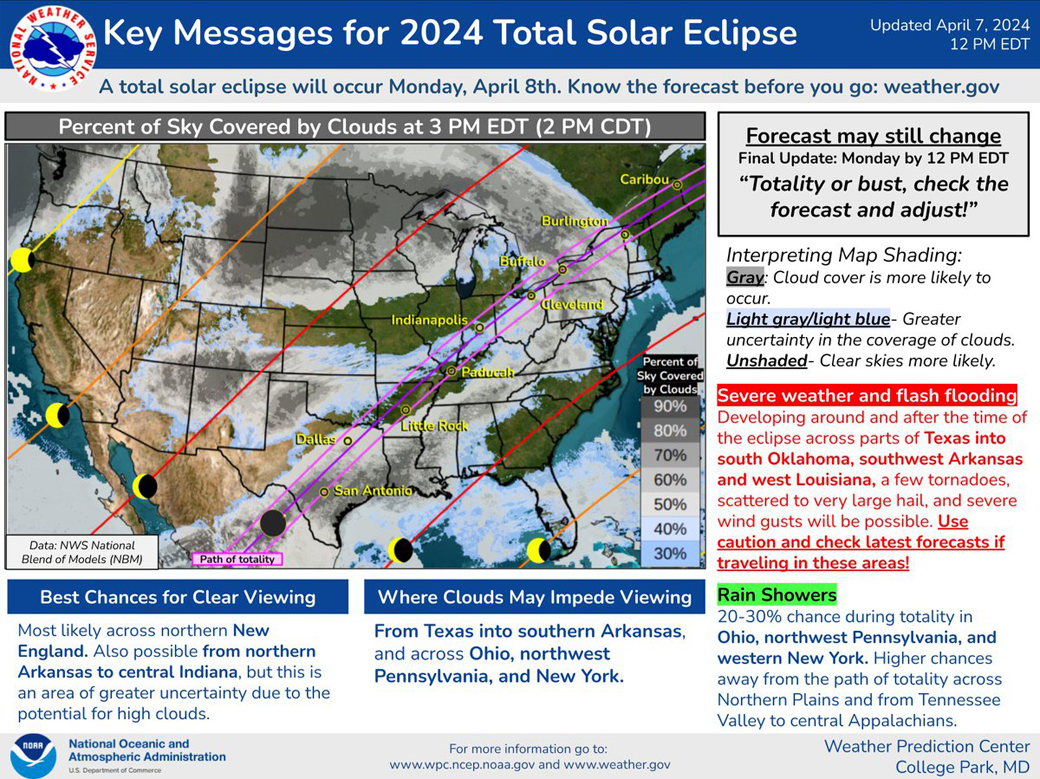

As early as a week before the eclipse, the National Weather Service was forecasting cloudy skies and storms for Texas and sunny skies for northern New England and upstate New York. Over the next few days, the outlook for Texas seemed to improve a bit, but the overall gloomy consensus remained relatively unchanged. By April 8, the forecast had once again deteriorated for Texas, with hail and tornados now a possibility.

Personally, I had made plans to view the eclipse in Texas. And why wouldn't I have? The smart eclipse chaser almost always heeds long-term projections based on historical weather data. As we ultimately saw on April 8, those projections sometimes don't mean squat, but it's still a wise starting point when planning an eclipse trip years in advance.

I didn't make a final decision about whether to change my travel plans until a few days before the eclipse. By then, I had concluded that my chances of seeing totality in Texas were slim to none. Conveniently, I have a relative who lives in the Adirondacks in upstate New York, where the forecast was still looking very good. I've been telling people for years now that staying flexible and mobile is the best way to prevent clouds and bad weather from spoiling a successful eclipse viewing. Now practicing what I preach, I cancelled my trip to Texas and headed to New York.

Unfortunately, by the time eclipse day arrived, the cheery forecast for upstate New York had waned just a bit. The weather front that I was hoping to stay ahead of had shifted to the east and my viewing location was now directly under the dreaded cloud mass seen on the National Weather Service eclipse map.

According to the map, northern Vermont was now on the leading edge of that eastward-moving mass. From where I was, I estimated it would be a two-hour drive to completely clear skies in Vermont. Having already shifted from Plan A to Plan B, it was now time to launch Plan C. Vermont would be my final viewing site.

When I got there ("there" being a random town near the eclipse centerline that I spotted on Google Maps before I left), the skies were mostly clear as promised. But I apparently couldn't quite outrun that approaching cloud front. There it was, coming in from the west, covering about a quarter of the sky... the precise quarter of the sky where the Sun happened to be! At this point, I could have jumped back in the car and kept driving east, maybe all the way to New Hampshire. But the problem was time. Or, more accurately, lack thereof. I had a couple of hours left before totality, but I still needed to find a suitable viewing spot. Clouds or no clouds, this would have to be my final destination. After a bit of driving around, I found a trailhead for a rail trail that ran through some open fields, hiked a short distance down the trail to where there were no people around, and settled in to wait for the big moment to arrive.

And that brings me to one of my biggest takeaways from the 2024 eclipse.

Of course, we all know that not all clouds are created equal. There are different types of clouds with different characteristics. It's obvious that thick, low-hanging stratus clouds (i.e., overcast) are the worst possible type of cloud for an eclipse viewing. Big, fluffy cumulous clouds aren't too bad. They float around fairly quickly and can even dissipate as the temperature begins to drop during an eclipse. But what about high, thin cirrus clouds? That's what I was facing in northern Vermont.

Up to this point, I've been very lucky with all of my past eclipse expeditions. Either I've enjoyed perfectly clear skies at my original viewing site or I've been able to relocate a short distance away to find them. In fact, this was the first eclipse that forced me to completely scrap my original plans. Since I really haven't had to contend with any clouds in the past, I wasn't quite sure what to expect with the cirrus clouds I was seeing in Vermont. And I couldn't ever remember reading anything about how cirrus clouds might effect an eclipse viewing.

The thin, wispy cirrus clouds you sometimes see that aren't even dense enough to obscure the blue of the sky would obviously pose no problem at all. But the cirrus clouds I was seeing were a lot thicker than that. As the clouds slowly moved east, they seemed to congeal and form a thick mass on the leading edge of the front.

By this time, the partial phase of the eclipse had begun and I was happy to see that the partially eclipsed Sun had no problem shining through the cirrus clouds. Even with the clouds, the Sun was bright enough that I could see my shadow and I could clearly see the crescent-shaped Sun through my eclipse glasses. But what would happen during totality? That was my concern. Would totality, which is 400,000 times less bright than a non-eclipsed Sun, still be bright enough to "shine" through those clouds? Would I only see the faint suggestion of the Sun's corona? Would I see anything at all? It was time to find out.

3...2...1...

Almost as if there were no clouds at all, there it was—a perfect vision of totality hanging in the sky, the solar corona pearlescing around a giant black hole where the Sun used to be.

As eclipse chasers, we instinctively think of clouds as the number one threat to be avoided at all costs. But this eclipse conclusively demonstrated that certain types of clouds are absolutely harmless. Unfortunately, the user-friendly weather maps and forecasts that most people rely on aren't very specific when it comes to clouds. Unless you're a weather fanatic (which I am not), who understands and knows where to find the most advanced and nuanced forecasting and modeling data, there's really no way to know what kinds of clouds can be expected on a certain day at a certain time. Yes, it's nice to know that 50 percent of the sky will contain clouds, but not knowing anything about the type of clouds is a serious problem when chasing an eclipse. Even the National Weather Service eclipse map was ambiguous to the point where you might assume overcast conditions were being forecast for much of the path of totality.

In the end, large portions of the eclipse path had the same kind of high, thin cirrus clouds that I had in northern Vermont. Indeed, I could have saved myself the time and effort by remaining back in New York. The folks in the Adirondacks enjoyed the same perfect viewing that I did in Vermont. Much of the middle of the country, including Arkansas, Missouri, Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio, had excellent viewing conditions. As for Texas, it ended up being a mixed bag. The storm clouds were more forgiving in certain parts of the state, offering quick peeks and hazy views, but other areas were less fortunate. Also missing out were eclipse watchers in Pennsylvania and western New York. And the best viewing of all? That was in Maine, the one state along the entire path of totality predicted to have the absolute worst chances for clear skies on April 8.

The Experience

I have a confession to make. In the minutes before totality, I almost swore off eclipses forever.

What am I doing here? I asked myself. I've been planning this eclipse trip for years, I've changed states three times in the past week, I'm standing here all by myself in the middle of nowhere, and for what? To see something for a measly three minutes that I've already seen before and that I'm not going to end up seeing anyway because of these clouds that I wasn't able to get away from? I told myself I was done with eclipses for good.

And then totality happened. And it was the greatest thing I ever saw. And I couldn't wait to see it again.

That's what a total solar eclipse does to you. If you haven't seen one in a few years, you may begin to forget what it was like. You can't remind yourself by looking at pictures or watching videos, because film can't begin to capture what you can see with your own eyes, not to mention all of your other senses. But when it's happening, it all comes flooding back.

With the exception of one stock photo taken by a professional photographer, I purposely haven't included any other total solar eclipse images, either of the eclipse itself or of the surrounding landscape during an eclipse, as part of this blog post. No photo can ever come close to the real deal. Unlike many eclipse chasers who also happen to be passionate about astrophotography in general or eclipse photography in particular, I don't pretend to know anything at all about taking good pictures and I don't have the expensive equipment to do so anyway. In fact, I tell people to resist the temptation of snapping a few pics with your smartphone during totality. The moment comes and goes so quickly that you really shouldn't be wasting precious seconds trying to take photos that aren't going to look good anyway. Inevitably, it's a hard temptation to resist, and I found myself doing the exact thing I tell others not to do. Stupidly, I probably wasted a good 30 seconds looking at my phone. I'm certainly not going to include any of my own crappy photos here when even the beautiful eclipse photos taken by professionals can't even do it justice.

After the eclipse was over, I began thinking about how difficult it is to describe the experience of a total solar eclipse to someone who has never seen one before. How do you describe something that is so unique that there's nothing else remotely similar to compare it with? If you were transported to the surface of another planet and then asked to explain what it was like when you came back, how could you do that when the experience has no comparable Earthly equivalent that can aid you in your description?

This inability to authentically describe a total solar eclipse is unfortunate, because it discourages people who have never seen one before from making an effort to get inside the path of totality on eclipse day. Having been unimpressed by your underwhelming description of how amazing totality is, they opt to view the eclipse from outside the totality zone. After the eclipse is over, they wonder what all the fuss was about. "That was kind of dull," they say. Yeah, it was kind of dull because all you saw was a boring, old partial solar eclipse! A 99% partial eclipse isn't 1% less impressive than a 100% total eclipse. It's 100% less impressive!

What's more, many people who have never seen a total solar eclipse think the experience is all about "darkness." This was perhaps epitomized best by former basketball great Charles Barkley when he said during an April 8 broadcast that the people standing outside watching the eclipse were "losers" and "idiots" because, "hey, we've all seen darkness before."

The actual total solar eclipse experience is about so much more than "darkness." I've decided that the best part of a total eclipse (well, maybe not better than the actual sight of totality itself) is the minute or so before totality occurs. This brief period of time is so bizarre that, again, it defies any attempt at an accurate description.

Typically, the easiest way to know when totality has begun and it's safe to look directly at the eclipse without your eclipse glasses is when you can no longer see any part of the Sun through your glasses. Personally, I've never seen the Sun blink out through my eclipse glasses, because that would mean I was missing everything else that was going on around me. In those final few moments before totality, your surroundings are transformed into the oddest twilight world you can imagine. This isn't a normal dawn or dusk twilight. It's a surreal, weirdly colored half-light that, frankly, doesn't belong on Planet Earth.

In addition, all of the other living creatures around you start freaking out (including the people). During the 2024 eclipse, as expected, I saw a flock of confused birds flying... somewhere. Crickets started chirping... at three o'clock in the afternoon. There was a farm across the road from where I was. Although I was too far away to notice, I'm sure the farm animals were behaving unusually.

At this point, things are happening so fast and becoming so strange that you forget what you should even be looking for. One of the lesser-known effects of a total solar eclipse are something called "shadow bands." This rarely seen phenomenon on the ground is reminiscent of the rippling patterns of light and shadow you see at the bottom of a pool on a sunny day. I saw them clearly during the 2017 eclipse. I know I didn't see them during the 2024 eclipse. But the funny thing is that I can't remember if I even remembered to look for them! There are so many different things happening in these frantic few seconds before totality, and your senses are being bombarded in so many strange ways, I think you actually lose your mind a little. Later, after the eclipse is over, you'll gradually start to remember seeing things that your conscious mind never registered in the moment.

And then, at the penultimate moment, it's as if someone in the heavens flicks a light switch to off. All of a sudden, the Sun is gone and you're standing in darkness with a ring of "sunrises" and "sunsets" all around you on the horizon. Yes, it's dark out, but it's not like any kind of dark you've ever seen before.

Plus, let's not forget about the sight of the actual eclipse itself! If the total solar eclipse experience was all about "darkness" and nothing more, how do you explain that alien planet, a big dark disk with a wispy white halo, that spontaneously materialized in our skies? During the 2024 eclipse, my mind was so overwhelmed by those incredible few moments before totality that for about ten seconds after totality began I actually forgot to look at the sky! Here I was, worrying that those clouds were going to obscure my view of the very best part of the eclipse, and I didn't even think to look right away. Like I said, I think an eclipse can make you a little crazy. When I finally did look, my relief was palpable.

On the subject of darkness, I will say that this was a very dark eclipse. As compared to the 2017 eclipse, for example, the day was noticeably darker during totality. And this makes sense. The 2024 eclipse was a much longer total eclipse than the one in 2017. Its maximum duration of totality was a very generous 4 minutes and 28 seconds as opposed to only 2 minutes and 40 seconds in 2017. It was longer because the Moon's shadow on the surface of the Earth was wider. A wider shadow means that it takes longer to sweep over you, assuming you're standing relatively close to the centerline. And it also means that the edge of the shadow, beyond which the Sun is still shining, is farther away. Hence, it's darker near the center.

There was also something else that made the 2024 eclipse especially memorable. During totality, several solar prominences were clearly visible with just the naked eye. One of them, on the bottom of the lunar limb, was particularly large. This was an unexpected surprise. These tiny pink blobs along the edge of the Moon, which in reality are enormous jets of plasma extending from the surface of the Sun for thousands of miles into space, are usually very difficult to see during totality without magnification. But almost everyone I asked after the eclipse said they saw them, even though many of them didn't quite know what they were seeing at the time.

The Conclusion

I believe the 2024 eclipse turned out to be the best total solar eclipse in America of the last 100 years. It was certainly the longest total solar eclipse in over a century, so maybe that's not saying much, but this eclipse really came through in the end. Besides the long duration, the weather cooperated along a relatively large portion of the eclipse path, the degree of darkness and weirdness surpassed that of 2017, and most viewers were able to catch a rare glimpse of several solar prominences during totality.

With my faith renewed in the awe-inspiring spectacle of a total solar eclipse, and my passion to chase them restored, I'm already looking forward to my next eclipse adventure. Unfortunately, the U.S. will have to endure a total solar eclipse drought for the next 20 years (nine years if you count northern Alaska), but there are some really good ones coming up in some really interesting and accessible places around the world over the next few years. An eclipse is always a good excuse to visit a new place. Now that 2024 is a wrap, it's time to look ahead to the future.